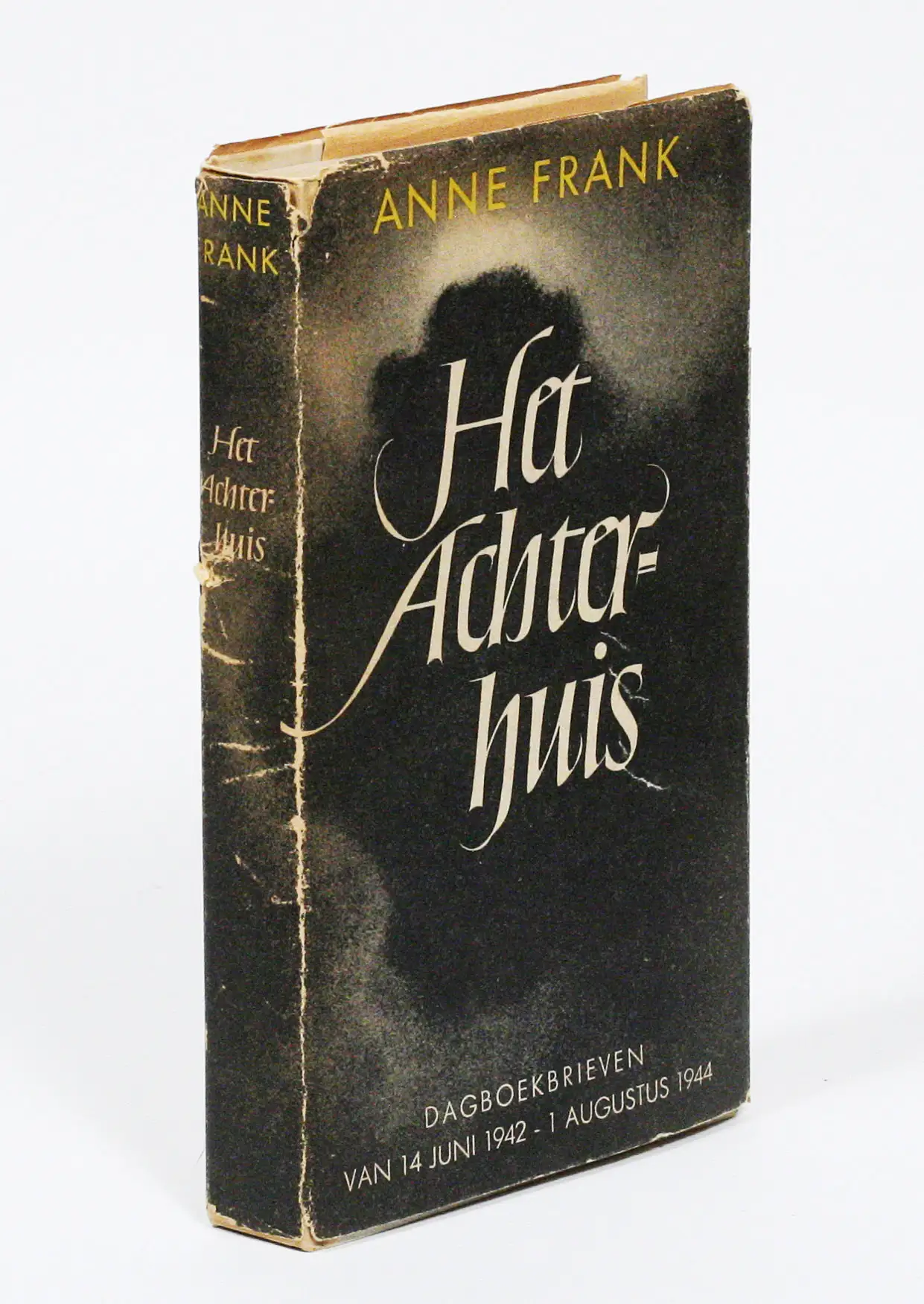

In two years in, Anne began writing her 150-plus entries in the hopes of eventually publishing them as The Secret Annex.

A Novel Idea

Two years in, Anne began writing her 150-plus entries in the hopes of eventually publishing them as The Secret Annex. Writing to Kitty in the diary was a creative outlet tor Anne Frank – but could it be even more?

On March 28, 1944, she heard a radio announcement made by Gerrit Bolkestein, the exiled Dutch minister of education and culture, about plans to publish wartime journals as documentation of the atrocities, so the “picture of Holland’s struggle for freedom be painted in its full depth and full glory.” Who better to add color than Anne? “Just imagine how interesting it would be If I were to publish a novel about the Secret Annex,” the 15-year-old mused in her diary the next day. “The title alone would make people think it was a detective story.”

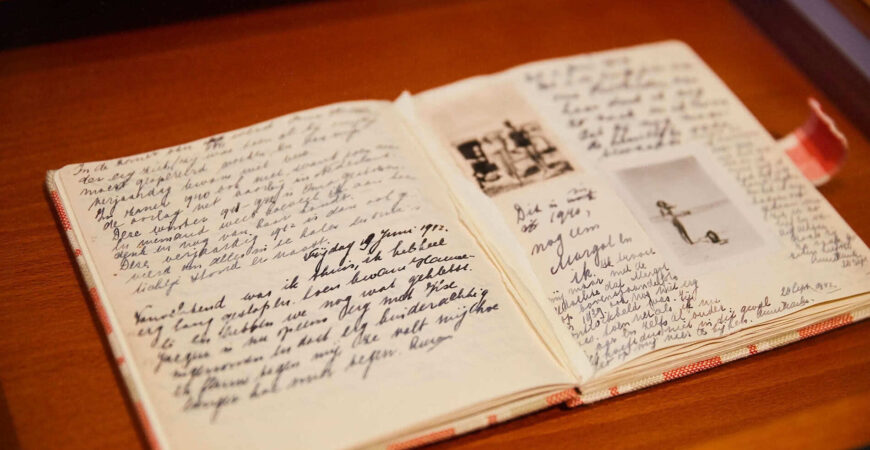

But there was nothing fictional about what was happening in German-occupied Europe. And if Anne’s diary was to serve as the basis of her book, it would need some serious editing. As she looked back at two year’s worth of entries, she realized much of it was “childish,” if not a little shallow: “Although I tell you a great deal about our lives, you still know very little about us.” So from that point on, she began the painstaking process of rewriting everything in her red-checkered diary and assorted notebooks, which she transferred onto more than 200 loose sheets of pink and blue paper that helpers Miep Gies and Bep Voskuijl provided for her.

By this time, Anne had greatly improved as a writer (see page 47), so the biggest edits ·were made to the entries from the first six months she kept the diary, from June to December 1942. As she reformatted the content to appeal to a wider audience, there were several topics she focused on modifying, such as her harsh critiques of her mother, Edith, and romantic feelings for Peter van Pels. As she reflected, she came to understand: “I hid inside myself, thought of no one but myself and calmly wrote down all my joy, sarcasm and sorrow in my diary.”

In the annex, the Frank family was often split into two camps: Anne and her father, Otto, in one; her sister, Margot, and mother in the other. On particularly rotten days, it could be three against one, with the youngest as the outlier. It was no secret Anne had a strained relationship with Edith, yet when she looked back at all she had written “dealing, with the subject of ‘Mother’ in such strong terms that 1 was shocked,” she admitted. “I said to myself, ‘Anne, is that really you talking about hate? Oh, Anne, how could you?”‘ She decided from that point on she would make a concerted effort to change, both in-person and in the pages of her diary. “The period of tearfully passing judgment on Mother is over. I’ve grown, wiser and Mother’s nerves are a bit steadier. Most of the time I manage to hold my tongue when I’m annoyed …. I soothe my conscience with the thought that it’s better for unkind words to be down on paper than for Mother to have to carry them around in her heart.”

Perhaps for that reason, Anne excluded a passage from Jan. 6, 1944, when she revisited “the subject of mother” to lament how Edith treats her more like a friend than a daughter. In Version B of the diary, the entry no longer included: “I need my mother as an example which I can follow, I want to be able to respect her and thought my mother is an example to me in most things, but she is precisely the kind of example that I do not want to follow.” (However, the sentence was put back in when the diary was published in 1947.)

The biggest change from Version A to Version B was in regards to Peter. Although Anne initially found the boy to be “nothing special,” by early 1944, after 17 months

in hiding, she began to look at him in a completely different light. And as the teens spent more time together, they developed a deeper bond-and eventually shared their first kiss one evening that April. But not long after, Anne was questioning her feelings for the brown-eyed boy and whether or not they had a genuine future after the war. As her emotions cooled, so did her revelations about Peter to Kitty-and hopefully one day, readers all around the world as well.

In the original diary entry for March 19, 1944, Anne described an intimate conversation she had with Peter clearing the air after the two had an argument. “We told each other so much, so very much, that I can’t repeat it all. But it felt good; it was the most wonderful evening I’ve ever had in the Annex …. I have the feeling that Peter and I share a secret. Whenever he looks at me with those eyes, with that smile and that wink, it’s as if a light goes on inside me. I hope things will stay like this and that we’ll have many, many more happy hours together.” Ultimately, she chose to omit the event completely from the revision.

Anne phased out much of her early and immature talk about puberty and menstruation. But there were several later entries she edited out as well, specifically in late March 1944, when she and Peter had candidly graphic conversations about sex. According to Anne, she and Margot “weren’t very well informed” by their parents on the topic, so the 17-year-old boy offered to enlighten her, which she gratefully accepted. “He described how contraceptives work, and I asked him very boldly how boys could tell they were grown up. He had to think about that one.” Later that night, “he told me how it is with boys. Slightly embarrassing, but still awfully nice to be able to discuss it with him. Neither he nor I had ever imagined we’d be able to talk so openly to a girl or a boy, respectively, about such intimate matters.”

During The Secret Annex project, Anne was naturally very protective of her work both the juvenile early entries and refined edits as a seasoned, writer. Miep learned this the hard way one day in July 1944 when she accidentally walked in while Anne was deep in thought “with Kitty. “She’d never been anything but effusive, admiring, and adoring with me, but I saw a look on her face at this moment that I’d never seen before; the helper recalled in her 1987 memoir, Anne Frank Remembered. “It was a look of dark concentration …. This look pierced me, and I was speechless. She was suddenly another person there writing at the table”

Miep was shocked when Anne slammed the diary shut and stormed out of the room, but she also understood. “I knew that more and more her diary had become her life. It was as if had interrupted an intimate moment in a very, very private friendship”