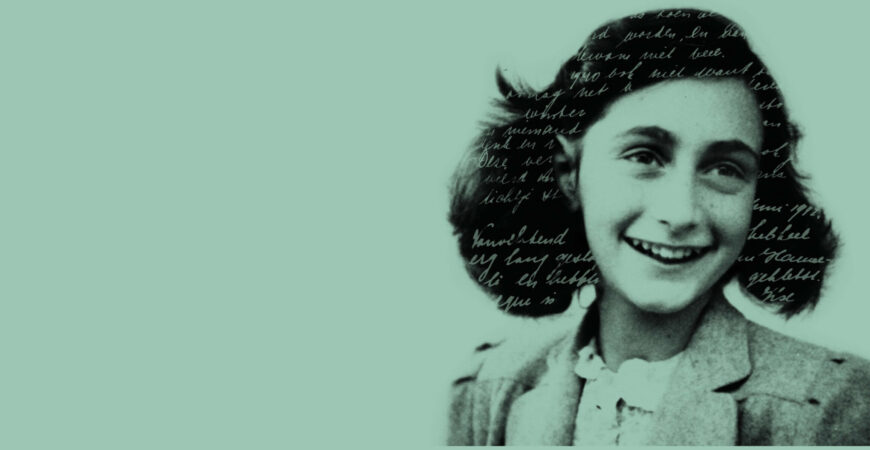

The Franks went into hiding so unexpectedly, Anne didn’t get a chance to say goodbye to any of her friends. The popular girl had always prided herself on the large clique (including several male admirers), both at school and around the neighborhood. Now cut off from them, lonelv Anne invented a group of imaginary friends–all of whom she wrote to as if they were real.

In addition to the most notable, Kitty, there was also Jettje, Emmy, Marianne, Pien and Conny. “I would just love to correspond with somebody, so that is what I intend to do in the future with my diary. I shall write it from now on in letter form” she wrote on Sept. 21. 1942. more than two months atter entering the Secret Annex. Pretending as if the entries were genuine personal notes, she addressed the majority “Dear Kitty” and signed each “Yours, Anne.”

Writing to her imaginary pen pals certainly filled the void, but it was just a temporary distraction from reality. Many times over the 761 days in hiding, she had moments of despair, which she detailed in the diary. “I feel wicked sleeping in a warm bed, while somewhere out there mv dearest friends are dropping from exhaustion or being knocked to the ground,” she wrote on Nov. 19, 1942, after hearing stories about how Jews not as fortunate were being treated by the Nazis occupying Amsterdam. “I get frightened myself when I think of close friends who are now at the merev of the cruelest monsters ever to stalk the earth.” Locked away inside the annex, the hiding place was especially secret. Attached to the rear of Otto Frank’s office building, it could not be seen from Prinsengracht, one of Amsterdam’s most popular streets, and its three other sides were obscured from view by surrounding buildings and trees.

Even from the inside of Opekta, the annex was nearly impossible to find. It was a maze of corridors, ankle-twisting staircases and offices just to arrive at the entrance, located in an unused area employees had no need to visit. “No one would ever suspect there were so man roon behind that plain gray door,” explained Anne. But just in case, a few weeks after they went into hiding, a bookcase was built to conceal the annex’s sole entrance and it swung open on a hinge like a door. Anne felt safe inside the 500-square-foot space, but it was a far cry from the Franks’ cozy home of nearly a decade just 2 miles away. During those early days in the annex, food was bountiful despite eight mouths to feed: three meals a day consisting of meat, fresh vegetables and fruit, beans, bread and bottled milk. Breakfast was hot cereal and fried potatoes, with lunch something light like soup and dinner usually a hot meal. “In the three months since I’ve been here, I’ve gained 19 pounds, Anne reported, along with everyone else’s healthy weights.

In the event they fell on hard times, there was an emergency stash of provisions: They canned “loads of rhubarb, strawberries and cherries” and purchased 300 pounds of beans and a large amount of meat, which Hermann van Pels preserved and made into bratwurst and sausage. By spring 1943, nearly a year in the annex, as the Netherlands was hit by famine, the quantity and quality of their food diminished considerably. They relied heavily on their supply of brown and navy beans, “just thinking about them makes me sick,” said Anne. In an April 27 entry, she added, “Our food is terrible. Breakfast consists of plain. un buttered bread and ersatz coffee.

For the last two weeks lunch has been either spinach or cooked lettuce with huge potatoes that have a rotten, sweetish taste.” As vegetables got harder to come by, they pickled what thev had, even if it was spoiled. The kale particularly needed to be consumed with a handkerchief to the nose to conceal its putrid stench. When there was a bread shortage in early 1944, they ate potatoes at every meal: fried for breakfast, kugel for lunch and dumpling, with imitation gravy for dinner.

The latter described Anne, were “so gluey and tough that it feels as if you have rocks in your stomach, but oh well! The high point is low. weekly slice of liverwurst, and the jam on our unbuttered bread. But we’re still alive and much of the time it still tastes good too!’ As the situation worsened, they had to skin breakfast altogether and eat hot cereal for lunch. The dinner meal would then be fried potatoes, and if they were lucky, vegetables once or twice a week. “That’s all there is” Anne revealed on May 25, 1944, nearly two years in hiding. “We’re going to be hungry, but nothing’s worse than being caught.”

As the Jews in hiding essentially didn’t exist. they had to purchase ration coupons on the black market. And as the war progressed, the price went up and up-doubling from 33 guilders each in November 1942 to 60 guilders at the start of 1944. Ahead of going into the annex, Otto and Hermann had saved money for the care of their families, yet over the extended period of hiding it was necessary for Opekta to contribute. To generate extra cash, helper Victor Kugler would sometimes not enter sales into the official accounts. There was a terrifying close call in March 1944 when the people who supplied their ration books were arrested.

“So we have just our five black-market ration books- no coupons. no fats and oils, reported Anne. Luckily, within two weeks the “coupon men” were released from jail and they could receive food again: “Things are more or less back to normal here.” At some point, everyone in the annex got sick, whether it was a flu or stomachache- yet they were unable to visit a doctor. Within days of going into hiding, Margot Frank came down with a bad cold, and her coughing was so loud, they feared someone outside the annex might hear.

At night, she was given large doses of codeine to coat her throat and help her sleep. Next, Otto was plagued by a high fever and covered in spots. “I’m very worried,” admitted Anne. “It looks like measles. Mother is making him perspire in hopes of sweating out the fever.” When Anne eventually came down with a cold. to quiet her nagging cough, “I had to drink milk with honey, sugar or cough drops. I get dizzy just thinking about all the cures I’ve been subjected to: sweating out the fever, steam treatment, wet compresses, dry compresses, hot drinks, swabbing my throat, lying still, heating pad, hot-water bottles, lemonade and, every two hours, the thermometer… Being sick here is dreadful.”

Preventative care was just as unpleasant. Fritz Pfeffer, a dentist back in his native Germany, brought his instruments into the annex to fill cavities or pull bad teeth. But in June 1944, 15-year-old Anne required a much more invasive root canal. The pain was so excruciating that Fritz-who used cologne as a disinfectant “thought I was going to faint” she told Kitty, “and I nearly did.’ Anne spent long hours reading to pass the time, and as a result her eyesight eventually needed correcting. Edith Frank suggested her daughter be taken to an ophthalmologist for an exam and possibly glasses by the wife of helper Johannes Kleiman. “Just hearing this made my knees weak, since it’s no small matter.” Anne revealed on July 11, 1943. “Going outside! Just think of it, walking down the street! I can’t imagine it. I was petrified at first, and then glad.” (Ultimately, it was decided she wouldn’t risk capture just to visit the eye doctor.)

Another time, Anne got her little toe stuck in the vacuum cleaner. “It bled and hurt, but my other ailments were already causing me so much trouble that I let this one slide, which was stupid of me, because now I’m walking around with an infected toe.

What with the salve, the gauze and the tape, I can’t get my heavenly new shoe on my foot.” Life in hiding was always supposed to be temporary. Anne, Margot and Peter van Pels brought along many of their schoolbooks in the hopes that after a few months or so, the war would end and they’d return to the classroom. Otto often acted as their substitute teacher, ensuring the three youths kept up with their studies. Anne focused on French, history (her favorite subject), geography and “wretched” math. “Daddy thinks it’s awful too. I’m almost better at it than he is, though in fact neither of us is any good, so we always have to call on Margot’s help.? Anne especially despised algebra and was disappointed that it “wasn’t entirely ruined” when someone spilled water on her textbook. “I wish it had fallen right in the vase. I’ve never loathed any book as much as that one.” When she wasn’t studying, Anne had her nose in a book- yet one of her choosing.

The teen was a fan of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales and Greek and Roman mythology, as well as young adult literature like Eva’s Youth, which touched on topics like menstruation and conception, and the Joop ter Heul series about a spirited girl whose “ludicrous situations still make me laugh.” Thanks to the helpers who made weekly trips to the library, Anne always had something to read, including less educational material like Cinema 8 Theater magazine (Victor brought her the latest issue every Monday). The safeguarding of everyone in the Secret Annex was an efficient operation, yet the threat of being discovered always loomed.

The first close call happened just months after going into hiding when a handyman showed up unannounced and began hammering away on the other side of the bookcase. From the inside, Anne listened in terror as the man continued to knock, push, pull and jerk the door. “I was so scared I nearly fainted at the thought of this total stranger managing to discover our wonderful hiding place,” she recounted on Oct. 20, 1942. “Just when I thought my days were numbered, we heard Mr. Kleiman’s voice saying, ‘Open up, it’s me. I can’t tell you how relieved I was. In my imagination, the man I thought was trying to get inside the Secret Annex had kept growing and growing until he’d become not only a giant but also the cruelest Fascist in the world.

Whew. Fortunately, everything worked out all right, at least this time.” Just four months later, the hiding spot was nearly blown when the owners of 263 Prinsengracht sold off the property without telling Johannes or Victor. One morning in February 1943, the new landlord showed up with their architect to survey the building. Fortunately, Johannes was already at work and volunteered to personally show the men around the building. But what about the attached annex? Johannes claimed he had left the key at home, which they didn’t question.

If the new owner returned and demanded to see the space, “we’ll be in big trouble,” worried Anne. Luckily, they never did. As scary as it could be inside the annex, outside was exponentially more dangerous not just in Amsterdam, but throughout all of German-occupied Europe (including Poland, Denmark, Norway, France and Greece). By the start of 1943, the Nazis were well on their way to “cleansing” the Netherlands of all its Jews, deporting them to concentration camps. Thousands remained in hiding, and the Nazis intended to find each and every one. The occupants in the annex stayed up-to-date on the progress of the war by reading newspapers brought upstairs by the helpers and listening to a small radio smuggled in by Johannes-and what they learned made them all the more desperate to never be discovered. “At any time of night and day, poor helpless people are being dragged out of their homes,” Anne wrote on Jan. 13. “Families are torn apart; men, women and children are separated.

Children come home from school to find that their parents have disappeared. Women return from shopping to find their houses sealed, their families gone. The Christians in Holland are also living in fear because their sons are being sent to Germany. Everyone is scared. Every night hundreds of planes pass over Holland on their way to German cities, to sow their bombs on German soil. Every hour hundreds, or maybe even thousands, of people are being killed in Russia and Africa. No one can keep out of the conflict, the entire world is at war.. In Amsterdam alone, the sound of gunfire became a nightly occurrence. Anne was so terrified, she often ran across the hall into the room her parents and Margot shared. “I still haven’t gotten over my fear of planes and shooting, and I crawl into Father’s bed nearly every night for comfort,” she admitted on March 10. “I know it sounds childish, but wait till it happens to you! The ack-ack guns make so much noise you can’t hear your own voice.” When Dutch workers went on strike that spring, all of the Netherlands was punished: Martial law was declared. On May 1, the gunfire outside was so relentless, Anne packed a suitcase in case they needed to flee the annex -and she grabbed it four times believing the time had come.

The unrest wasn’t only at night. Sirens routinely went off throughout the day to warn of enemy aircraft overhead. On July 25, 1943, the same day Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport was attacked in an air raid by Allied forces, “the house shook and the bombs kept falling, recalled Anne, who was clutching her escape bag. “The planes dived and climbed, the air was abuzz with the drone of engines. It was very scary, and the whole time I kept thinking, Here it comes, this is it.’ I can assure you that when I went to bed at nine, my legs were still shaking. As they approached two years in the annex, Anne vicariously learned the consequence for disobeying Nazi rule when Mr. van Hoeven, who supplied their fresh fruits and vegetables, was arrested for hiding Jews.

“The world’s been turned upside down,” she lamented on May 25, 1944. “The most decent people are being sent to concentration camps, prisons and lonely cells, while the lowest of the low rule over young and old, rich and poor.. Unless you’re a Nazi, you don’t know what’s going to happen to you from one day to the next.” Paralyzed by the possibilities, everyone in the annex practically lived in silence-yet nothing could quiet Anne’s thoughts. “What will we do if we’re ever…no, I mustn’t write that down. But the question won’t let itself be pushed to the back of my mind today; on the contrary, all the fear I’ve ever felt is looming before me in all its horror.”