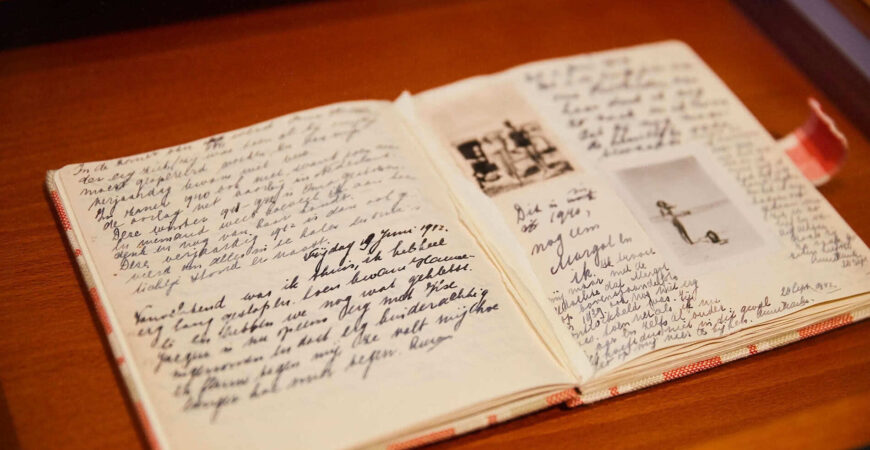

On March 29, 1944, Anne hears a radio broadcast by Gerrit Bolkestein, Minister of education, art and science of the exiled Dutch government in London. He speaks of his plans to collect and publish personal testimonials such as letters and diaries to help people understand how the Dutch were oppressed by the German occupiers during the war. He suggests that Dutch citizens should preserve such documents and hand them over to the Dutch government after the war.

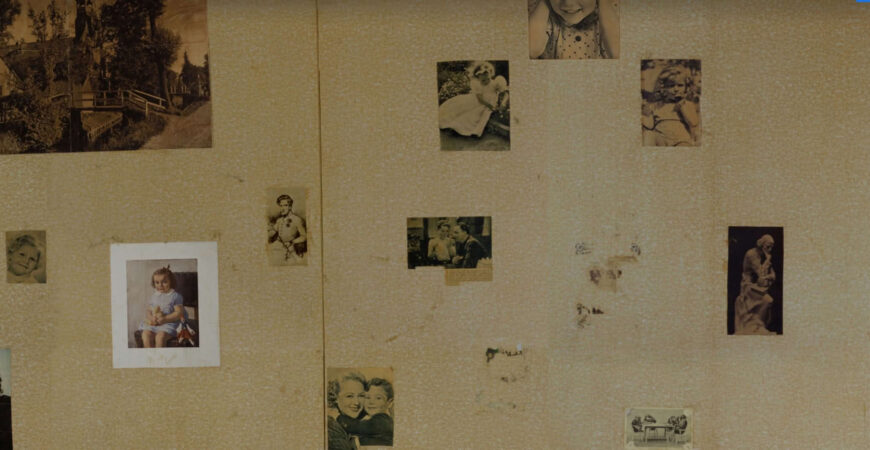

Anne, who already wanted to become a journalist or a writer previously, likes the idea. She starts editing her diary for later publication. Anne plans a novel entitled Het Achterhuis (The Secret Annex). To preserve the anonymity of the people living with her, she thinks up pseudonyms: the Van Pels family become the Van Daan family, and she calls the dentist Fritz Pfeffer, with whom she has frequent run-ins, Albert Dussel (“idiot” in German). She turns her own family name into Robin or Aulis, but this name is not used in the published versions of the diary.

How did Anne Frank’s diary become one of the most read, most important and most inspiring books in the world?

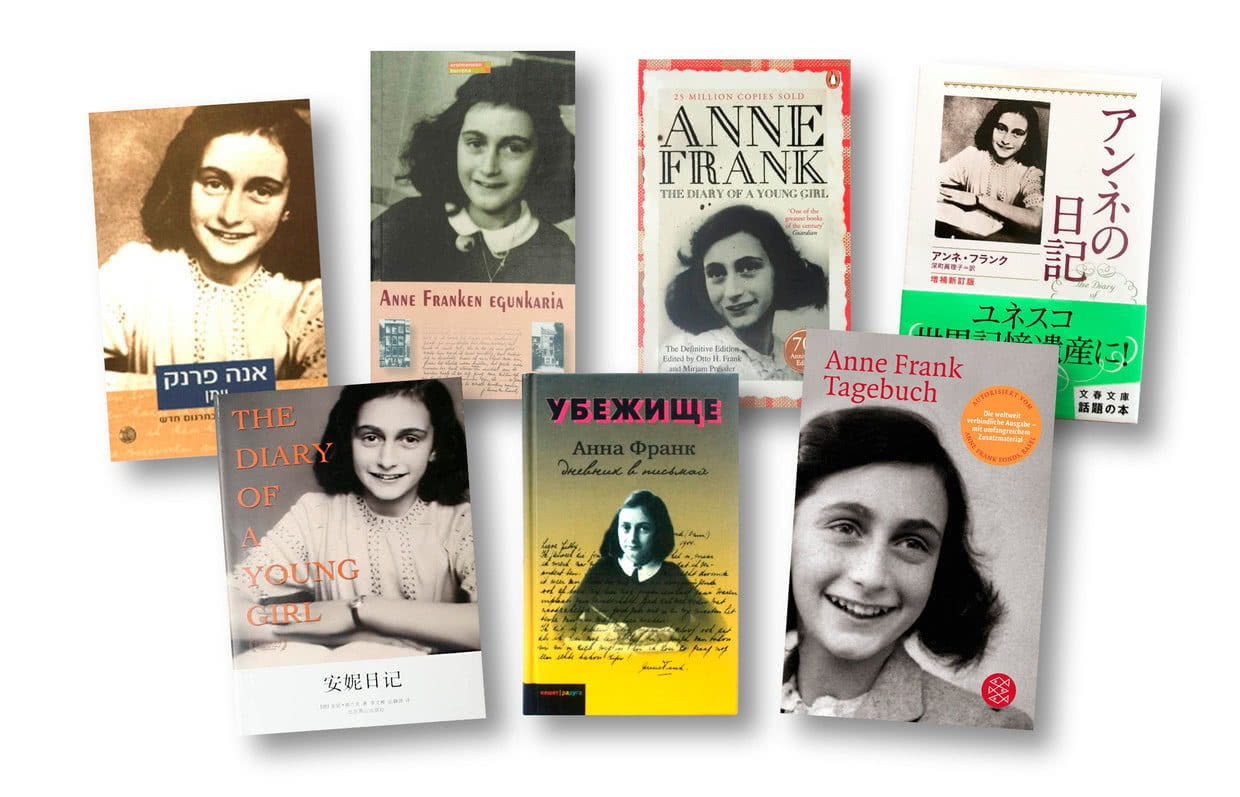

On 25 June 1947, Anne Frank’s Het Achterhuis (The Secret Annex) was published in Dutch in a small edition of 3,036 copies.

After the success of the Dutch edition, Otto Frank found publishers in West Germany (the Federal Republic of Germany) and in France willing to publish Het Achterhuis. Both translations were published in 1950. A first edition of 4,600 copies was printed in Germany, but the book was not a bestseller. However, when Das Tagebuch der Anne Frank was published as a cheap pocket in 1955, it became a hit.

Success in the US after review in The New York Times (1952)

In 1950, after reading the French edition, Meyer Levin first wrote about Het Achterhuis in an article on ‘the attitude of American publishers towards books of Jewish content’ for Congress Weekly magazine. He called Anne Frank a ‘highly gifted writer’ and her diary ‘a work about the unfolding of the nature of a young girl absolutely pure in candor and at the same time in delicacy.’

Otto had a hard time finding a publisher in the United States. After the manuscript had been turned down by 10 publishers, Doubleday publishers decided to acquire the rights. The publication of Anne’s diary in America in 1952 had a cautious start. Five years after the book was first published in the Netherlands, Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl was launched in a modest edition of 5,000 copies.

“I once asked my publisher why he thought the diary was read by so many people. He felt that the diary covered so many areas of life that every reader found something in it that affected him personally.”

Otto Frank, ‘Memories of Anne’ 1968.

Doubleday did not hold high expectations and hardly spent any money on additional advertising. Sales did not go well. But after an enthusiastic review by Meyer Levin in The New York Times Book Review (15 June 1952), sales began to pick up. A second print run of 15,000 copies was issued, followed within days by a third of 45,000 copies. Before long, print run after print run sold out in rapid succession and millions of Americans read the book.