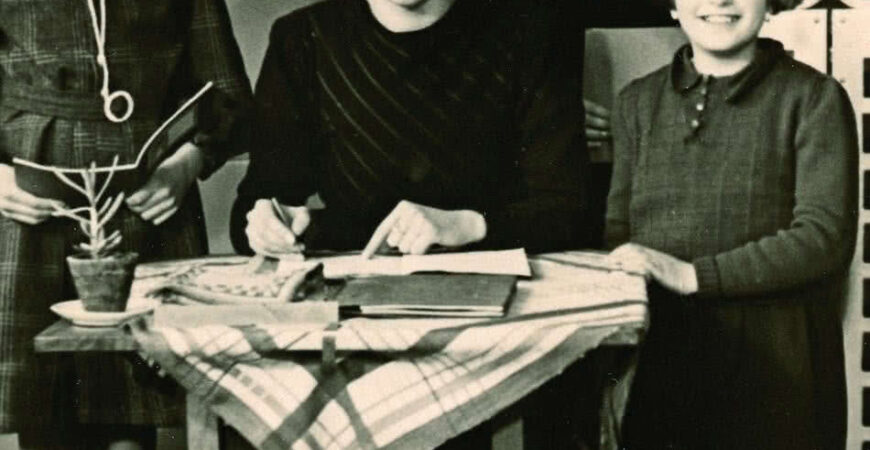

On July 5, 1942, Anne hung out with new friend Hello Silberberg and spoke on the phone to Jacque van Maarsen

In the summer of 1942, Anne Frank’s large group of friends had a new face: Hello Silberberg, a 16-year-old Jewish boy who had escaped Nazi Germany four years earlier and lived with his grandparents in Amsterdam. Anne and Hello, the second cousin of her friend Wilma, instantly clicked and the inseparable pair enjoyed walks around the neighborhood. But he wasn’t just another of her many male admirers. “Hello and I have gotten to know each other very well this past week, and he’s told me a lot about his life,” she gushed on July 1.”In everything he says or does, I can see that Hello is in love with me, and it’s kind of nice for a change.’

Four days later, as Anne was writing in her diary about a concerning conversation she had with her father about going into hiding, there was a welcomed disruption: “The doorbell’s ringing, Hello’s here, time to stop.” The teens spent the morning on the Franks’ balcony, chatting and enjoying the summer sun. At lunchtime, Hello went home to eat with his grandparents, but promised he’d return that afternoon. While Anne waited, she curled up with a book as her mother and Margot worked in the kitchen. Otto headed out to visit a friend in the hospital in Weesperstraat, located about 2 miles away.

As expected, at 3 p.m. the doorbell rang-but it wasn’t Hello. Instead, the postman delivered a registered letter requiring Edith’s signature. Shortly after, a “very agitated” Margot joined her sister on the balcony with terrible news: “Father has received a call-up notice from the SS [Nazi paramilitary],” she whispered. Anne feared the worst. “Everyone knows what that means. Visions of concentration camps and lonely cells raced through my head.” Otto’s prediction was now an immediate reality. As the escape plan went into motion, the girls were sent to their room, where Margot shocked Anne a second time with the truth: The notice was actually for her. “I began to cry. Margot is sixteen-apparently they want to send girls her age away on their own. But thank goodness she won’t be going; Mother had said so herself, which must be what Father had meant when he talked to me about our going into hiding. Hiding … where would we hide? In the city? In the country? In a house? In a shack? When, where, how …? ” Without any answers, Anne and Margot began packing their most precious belongings. At some point that evening, Anne’s best friend, Jacque van Maarsen, called, but Edith warned her daughter not to say a word. Once Otto came home from the hospital and learned what had transpired, Miep Gies, one of his trusted employees, was summoned to the apartment along with her husband, Jan, to collect some of the Franks’ belongings. “No Jew in our situation would dare leave the house with a suitcase full of clothes, “Anne explained in her diary. As she packed her schoolbag, “The first thing I stuck in was this diary, and then curlers, handkerchiefs, schoolbooks, a comb and some old letters. Memories mean more to me than dresses.”

Miep and Jan carried everything back to their home (with the plan to bring it to the annex at a later time), then returned to the Franks for a second collection of shoes, stockings, books and underwear. But when they arrived, Anne tried to pass off too many things. “Mrs. Frank told her to take them back,” Miep wrote in her 1987 memoir, Anne Frank Remembered .”Anne’s eyes were like saucers, a mixture of excitement and terrible fright.”

At 11:30 p.m., eight hours since her life changed in an instant, Anne laid down. “I was exhausted,” she recalled to Kitty, “and even though I knew it’d be my last night in my own bed, I fell asleep right away and didn’t wake up until Mother called me at five-thirty the next morning.”